- Nasturtium and Cosmos

- Posts

- The Best Orange

The Best Orange

On context and color.

The other day a student asked me what my favorite color was. This happens every so often—high school students these kinds of have pre-loaded questions to which they ascribe heavy importance (See also: “Where do you fall in your family’s birth order?” “Do you believe in ghosts?” “Do you have TikTok?”). Oftentimes, when a student asks me this, I lie and just say whichever color came to mind first, mostly to keep moving the conversation along (this question is often posed as a stalling tactic because students are canny and have a robust toolkit of diversion strategies), but on this day, I answered the student’s question honestly, which is to say, I disappointed them: I do not have a favorite color because, to me, color only makes sense in context.

“That doesn’t make any sense! Just pick one. You seem like you’d like orange.”

“Orange!? Why?”

“Orange is, like, lowkey aggressive, you know? And you seem like someone who likes aggressive colors.”

(A good deal of my day is spent incurring unintentional insults from teenagers. I have, over time, developed an armadillo-like armor against dopy aspersions.)

“I am sorry to disappoint. But orange ain’t it. Though, I do like orange sometimes! It just depends on the situation.”

And this is where I ruin a kid’s day because I turn it into a whole thing. And they hate when I do that—except that they secretly love it.

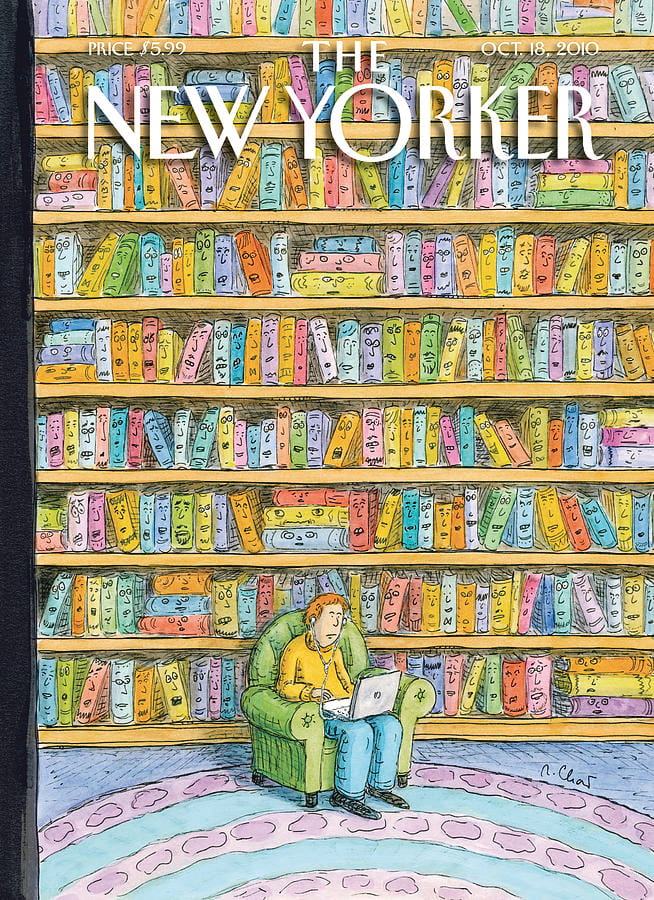

In my classroom, I have a bunch of New Yorker covers from a 2015 New Yorker calendar hanging on my bulletin board because, though I’ve been asking for whiteboards to replace those bulletin boards for years now, I still have beige bulletin boards covering the entire southern wall of my classroom, and I have to cover them with something. So these New Yorker covers feature the work of some of the great illustrators that dapple the magazine’s history like Roz Chast, Edward Gorey, and Saul Steinberg. Year after year, I’ve tacked them to the bulletin board. They’ve survived mild sunbleaching and mild water damage (my ceiling has leaked various states of water multiple times over the years. I have a strange and sordid history of happening upon “water-related emergencies” at multiple jobs. Here at my current job has been no different. One such emergency involves me yelling “Active water! Active water!” at my boss until he got out of his seat and followed me to a burst pipe in the school book room because I’m not good in emergent situations and verbs are typically the first to go. But I digress. Again.). The posters are a perfect encapsulation of my own personal color theory: a color really isn’t a color unless you’re considering it with other colors. A color doesn’t really do anything interesting on its own in my mind. I need context to understand or enjoy it.

So I point to the one of the posters, the Roz Chast cover, and say, “See those sort of reddish-orange moments in the poster? The book spines? I like that orange. I like the way it pops against the more pastel-toned colors. That’s a good use of orange. I’m not sure I would be drawn to it out of context.”

The student regards the poster.

“So you do like orange. So I was right?”

“I like that orange. So yes. But also no? Like I said, it depends on the context. I’m not really into orange when it’s just a traffic cone on concrete, but I don’t dislike all versions of orange and gray, either!” I lean in conspiratorially. “There is a best orange. Would you like to know about the best orange?”

At this point, the student understands I have wrested the conversation from them and turned it into a treatise on my own interests. Teachers, like all humans, are selfish creatures. They roll their eyes and nod. Undeterred, I continue, fully alive.

“The best orange only occurs for about two weeks in late-October, early-November in Ohio during the fall. It requires the perfect alchemy of gray skies, orange leaves, black branches, and sunlight. This is the best orange. Because of the contrast. The orange doesn’t matter without that context.”

The Best Orange

The student considers this for a moment, and then says the thing students often say when they must concede that you, the teacher, might know something they hadn’t thought of before.

“Bro. That’s actually, like, deep, though.”

The word “actually” does a lot of work in that sentence. Indeed there is soft indignity buried in that “actually,” but it doesn’t change the fact that the student is pondering a shift in their own framework of meaning.

At this moment, the conversation dissolves into air because twelve German exchange students and the entire varsity softball team have entered my classroom for reasons that are as of yet unclear to me. And from here, the moment steals away, and any control I had over the day sizzles like a dying worm on pavement at high noon on a cloudless July day.

But it was a nice enough moment to earn 850 words.