- Nasturtium and Cosmos

- Posts

- The Machine Can Only Apologize

The Machine Can Only Apologize

On Listening and Learning

I can’t really remember what compelled me to purchase a pair of smart speakers in 2022 (The strange later days of the pandemic? Season 1 of Severance? Literal online influencing? Who can say?), but we (okay, fine: I) got this idea that we’d get a Google Nest and an Amazon Alexa, and there would be a quiet dystopian battle unfolding in our home for smart speaker supremacy. Plus, I wanted to a bluetooth speaker in the bathroom that had a clock on it (These exist, and it should be a sign of personal weakness that I didn’t just purchase a bluetooth speaker with a clock on it).

This was stupid and wasteful, of course. No one really needs one smart speaker, let alone two competing tangles of plastic, lithium, surveillance, etc.. But, click, type, CO2, ta-da: there were two of them—Google in the kitchen, Alexa in the bathroom—and our family of two humans, one dog, and two cats, expanded to include two small blue domes lousy with planned obsolescence. It was painless and relatively inexpensive and changed basically nothing about my immediate circumstances. Participating in the trappings of a middle class life is breathtakingly convenient—and boring.

Here’s the first thing I noticed about smart speakers: I mostly forget that they were there. They are designed to be unobtrusive, until they aren’t. Unless you noodle around in the Alexa app for a while, Alexa will tell you things. It lights up cautionary yellow until you relent: “Fine. What is it?” And then Alexa announces whatever information its little beeps and boops processed into necessity. “Anne, it looks like it might be time to reorder Fresh Step Cat Litter Multicat Cat Litter for Multiple Cats. Would you like me to add it to your cart?” I’ll confess here that the way Alexa says my name chills me to my core. The gentle horror and slowness of the way it pulls the first vowel like taffy reminds me of Ms. Cobel from Severance (“Maaaaaaahrk”): It’s a hug from a boa constrictor: kind of nice until you realize your brain is dying.

This is where Alexa has its first sinister edge on Google. Until you toggle this feature off, Alexa makes you remember its there. While the Google Nest gathers dust and cooking grease in the kitchen, Alexa gathers information (and dust) in the bathroom.

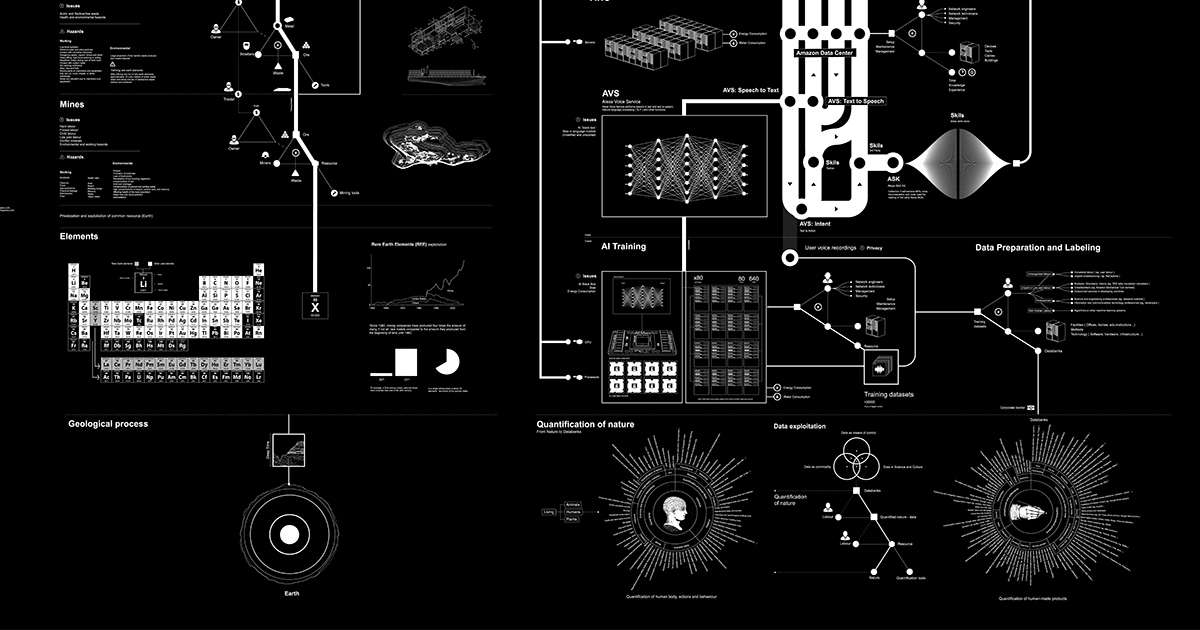

And when/if you eventually do toggle of Alexa’s existence insistence, Alexa still gathers information in a less obvious and, as of yesterday, more insidious way. Everything we say to Alexa will now be processed in the cloud as part of a larger effort to support Alexa’s newest iteration, Alexa+, a machine designed to learn everything for the low, low price of your privacy and labor. Alexa will be listening and learning at all times. But listening is a slippery verb in this context. What Alexa (or Nest or Siri or any speaker for that matter) does is a personified act. The “listening” in this case is a metaphor for something else, an acoustic processing masquerading as meaning-making. Because, of course, Alexa can’t make meaning.

This becomes clear every time I tell my car’s smart speaker to “Call [husband] on mobile,” and the machinic women’s voice responds, “I’m sorry. I didn’t get that. Please try saying that another way.” So, I try again, and the machinic voice, ever-so-contritely, apologizes for its lack of understanding. My husband’s name is unintelligible to her. I know what I want to do in this moment; I know the meaning behind my intention and behind my husband’s name. The command is simple, but the machine can’t understand the thing I’d like to do: to call my husband to decompress and vent about my day, to see about what we should make for dinner, to share language. But the machine can only apologize, or rather, produce language that intends apology because the machine doesn’t know what it is doing, only that it is or is not doing.

This is what Mark Andrejevic calls “operationalized listening.” These machines don’t listen to understand; they listen to do an operation, to perform a task, to produce an outcome. What does it mean to live in a world where speech becomes prompt, where we engage in speech that mimics kinship but fails the meaning test?

When my car’s smart speaker apologizes to me for failing to dial my husband’s phone number (is dial the right verb there? Unlikely), my response is to sass back: “Damnit, lady! What do you need me to say? ‘PHONE. CALL [HUSBAND.]’” My tone shifts to convey my frustration, as though that will shift the response, as though that means anything to the machine.

We talk to machines all the time. I’ve sung songs to my toaster. I tell my oven timer to can it. When the water is too hot from the faucet, I tell it, “Whoa girl, cool thyself.” I have told a little wall plug that it’s tiny surprised face was cute, because it was cute. We develop magical thinking about machines because humans are relational creatures, magpies all, who collect and relate and narrate and narrativize. But I think a problem arrises when the machine talks back. The imaginative space of person-ified machines breaks down when the machine suddenly performs humanity that isn’t actually human.

And this is where operationalized listening becomes a problem, and where I’m trying to write my way through my own anxiety about any AI technology whose dance card includes surveillance, false expertise, and intellectual theft. If you push your finger past the gossamer of convenience and novelty, there’s a lot to fret about in a world mediated by smart speakers. The muck beneath is just momentarily directionable noise—directionable because, while we “teach” the “listener” to respond in a desired way, the listener is really just Emily Bender’s stochastic parrot, the dove stuffed with sawdust and diamonds (to mix bird metaphors). We pour meaning into “there,” but there is no there there. The operationalized listener has the potential to do something fairly awful here, because again, humans are relational and language is a vector for relationship. The operationalized listener can start to teach back, or at least condition behaviors.

The operationalized listener is the ultimate perpetrator of that old conversation sin of listening to respond, or maybe it’s more like listening to react. We position these speakers as a service, and in many ways, the speaker does perform a service when prompted (“What’s the weather?” “Turn the volume up one” “Set a timer for 10 minutes” “Play Guardians radio”), but there’s ulterior profit in that service beyond what we’ve paid for (by speaking to the speaker, you do the unpaid work of teaching the AI, for example). The service is a reaction to a prompt, but the reaction doesn’t always match the prompt. As with GenAI technologies like ChatGPT, the party-line is often that the user needs to learn how to prompt the machine more effectively, it’s a skill issue on the part of the user. There’s this instinctive positioning of the machine as a stable interlocutor, and not only that but an expert, authoritative one.

I’m still working my way through where to pin the tail on the authoritarianism in all this, but when I step back far enough, it does start to feel like technologies that engage in operationalized listening have the potential to smuggle in mostly destructive ways of engaging with language in general.

If, through technologized erosion, language itself becomes more operationalized (especially in digital spaces), we risk losing our footing. Meaning-making becomes more difficult because operational listening by definition is not concerned with meaning. Or context. Or humans. When someone like Elon Musk condemns empathy as weakness, he does so with an eye toward removing a method of meaning-making (attempting to understand the emotions and lived experiences of another) that builds compassion and human connection. He’s already done an aces job of achieving this operationalized state of reactive cruelty on his own digital boondoggle over on X. No one can listen to understand in a space like that because the space has really only been built for one gross dude to force everyone to watch him engage in increasingly grotesque interactions with a world he’s manipulated in his image.

If all this seems a little gooey, it’s because I don’t think I’ve really figured any of this out. I readily welcome push- and feedback. I’m sure I’m ruminating unproductively about some of this, taking unnecessary leaps, and/or missing connections or larger issues at times. But I think all of this is important to consider critically because an uncritical adoption of these technologies cedes control of language (among other things) in ways that feel utterly dystopian to me, and I’d prefer my dystopias to live permanently on the page and in the imagination where they belong.